1963 Las Vegas Press Club has a Ball on Bases in Tonopah

This post may contain affiliate links or Google Ads and we may earn a small commission when you click on the links at no additional cost to you. As an Amazon Affiliate, we earn from qualifying purchases. This is at no additional cost to you and helps with our website expenses.

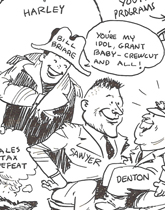

One thing I’ve learned most certainly from our found edition of the 1963 Las Vegas Press Club Branding Iron magazine is that the old Press Club could party and play with the best of them. Writer Joe Digles wrote a humorous review of a trip to Tonopah for a baseball game with their rival the Capital Press Club. Enjoy!

A Ball on Bases in Tonopah

By Joe Digles

They moved out under sunlight.

Surprise was to be a key stratagem in the attack on Tonopah. Indeed the very appearance of 30 Press Clubbers in broad daylight surprised their leader. She carried through the artifice. Dressed in a mu-mu, Jay Hamann directed the heavy-loaded band into the bus. The carrier lurched northward toward the mission, amid the muffled rattle of aspirin. The time was 8:16 of a Sunday morning, or less than 34 hours since the Press Club barroom doors had slammed on them.

Destination was Tonopah, land of the four-legged jackass, a multiple or mutation of the species they had grown to endure in Las Vegas. Object was the annihilation of Capital Press Club. Weapons had been chosen—bats and balls—and a battlefield, selected the dust-encrusted acres of Logan Memorial Field hard by the once ore-rich hills soon to echo with the profanities of a later time.

At 8:21, to the windward of Vegas Heights, a familiar cry was sounded. It blended with the peal outside of church bells calling the faithful. “The bar is now open,” declared Leon Potter. He commanded awe. Astride two sweats, his form billowed impressively as would that of a potentate or bartender or similar object of adoration. The ashen-faced attackers responded by instinct. The solemn nature of their mission was indicated, perhaps, by the reticence of their leader. She did NOT shout: “Wine for my men, they ride tonight!”

No, the cause was too grim for banality. The accouterments of battle gave testimony to that. The men were draped with weapons of warfare—cudgels, steel masks, and spiked shoes. Their women wore capris pants to demonstrate the weight of the affair.

The plan called for a tactful beguiling of the natives en route to attack the area. The bus jolted to a stop at Indian Springs and disgorged its burden to mingle with the villagers there. All effort was made to befriend the natives, even to the point of partaking of their beverage, a murky, alcohol-free substance called coffee. Somewhat weakened by the odors and tastes of this aborigine squatting place, the Press Clubbers eventually found their way back to the bus bar. The bus door clanged despite one errant hand. Beady-eyed, they squinted northward toward the foe.

The warriors assuaged their tensions by generous hoisting of latter-day flagons. Ribaldry reminiscent of the Press Club cocktail hour (3 to 11, Monday through Friday) pervaded the atmosphere. Harry Parker brandished a deck of playing cards—returned to him after a raid on the Desert Inn tables and sounded the call to poker. Others playfully wrestled for a good spot in the line to the bar. Some attempted to pit sleep against the effects of inherited hangovers. Still others gaped, noses pressed against the windows, at the quaint peasantry of Goldfield. Our driver, Carl, pressed on, cleverly aware that not all the red lights we encountered were traffic signals.

Suddenly the skyline of Tonopah loomed ahead. Yes, it did have all making of a battlefield. Or at least it bore the scars of some tumultuous struggle. Unbelieving eyes glinted at us through pitted walls; jiggers crashed to a barroom floors as stunned inhabitants pushed for furtive glimpses of the metal monster that bore us up a foothill whence we roared to a halt in front of the Lions Club.

Catcalls and threats hailed the Las Vegans as we stepped out on Tonopah soil. The enemy had arrived earlier and it was their profanity being hurled through the blue fog of their cigar smoke. Truly they epitomized the legendary evil. A more debauched group might only be found applying for a state gaming license. Wine-red eyes squinted contemptuously from faces long since puffed by Carson City orgies at the public through. Fingers grown fleshy from dart-throwing during working hours offered us flabby handshakes. Truly could there be a greater cause? Could there be a more pronounced situation of good versus evil? Our destiny was to dash into the dust these image-makers.

Before attending to the commands of destiny, we bellied up to the Lions Club bar where our host Ira Jacobson supervised the dispensing of booze with all the rustic urbanity of Ernie Ford. Vintage redeye sloshed in roasts designed to lull the enemy into ill-founded illusions of security. Giddy with delight over our trickery and its imminent success, we swaggered to the tables prepared for a pre-game feast. As the bones flew over our shoulders, we pricked the consciences of our rivals with pro-Laxalt jokes and job offers or the governor and his minions as a device for state economy. Black rages were evoked, as was the plan.

Filled with the spirit of battle, we hurtled back into the sunlight to don mustard-and-blue tee shirts, blue caps and grim countenances. Contents of the bar were loaded into a pickup truck and bottles and baseball players rattled off to Logan Field.

Our warm-up was brief but spectacular. It consisted primarily of removing boulders from the playing field. There was one pre-game casualty. An outfielder who couldn’t even spell bagnio disappeared in a ravine behind the right-field boundary and kept going in the direction of a place where someone could surely tell him how to spell it.

Don Beale took the mound for the Las Vegas Press Club. He must have liked it—he was there so long. Despite moral support from this fielders—sounds like the curses heard when the miners found the pay stage had been held up—Beal’s rightist deliveries placed the ball squarely on the bats of the opposition leftists. The strategy had been to allow the Carson City gang to wear themselves out on the bases, but this was going too far.

Finally, a third out was recorded. Manager Hamann, her muumuu left limp after exhortations to destroy the enemy attack, now summoned us to contribute all our efforts. “Pay of the umpire,” she whispered in the ears of prospective batsmen. This ruse failed, but thanks to the blunders of the opposition the Press Clubbers mounted an attack that came close to wedding our score with theirs.

The events of the succeeding six innings will never be faithful recorded. The inroads of heat, hops, and feelings of hilarity attributed to the Alpine altitude combined to make a blur of it. Some highlights are recalled, however. Bob Richards, a non-combatant, cheered us on from his position at the portable bar despite a whiskey-induced hoarseness. Bob Flick smashed a tremendous shot to the left field only to have the ball snared in the rear pocket of State Treasurer Mike Mirabelli (a pocket, it was reported later, once to have held his wallet and therefore roomy). Jimmy Williams and Don Schieck, both ringers, performed up to professional standards. Ben Fisher confounded the foe by whipping up sandwiches between pitches, and some faceless, nameless (for security reasons) individual strode to the plate wearing a Berkeley Bunker button to throw the opposition into confusion.

The final score remains a mystery. The scorecard was used to staunch a leak in a beer barrel. The sodden pulp became one of those forgotten footnotes of history. (Or do YOU know what ever became of the Dutch boy’s finger?)

An unconfirmed news release from the governor’s office a week after the game hinted that the Carson City team had won. The gaiety of post-game revelry at the Tonopah Club bar would not attest to that. Battle-stained by ever-testy, the Press Clubbers cleared the dust from their throats with Tonopah ambrosia. Their conduct gave tribute to their raucous behavior patterns.

All to soon it was time to board the bus for the return. Now snarling and glassy-eyed, the band cast a verbal question mark on the ability of the driver to cling to the ribbon of the highway. The near-miss of a cow gave credence to the argument, provoking hisses from the riders and muted boasts of motoring skills. Darkness soon encased the bus, trapping the foul air within and compressing the emotions unleashed by 12 hours of incessant internal lubrication.

Quicker than you can drive to Beatty and back, we were home. Weary of mind and body, we stumbled to the freedom of fresh air. Our movements, now by instinct, were of a sudden brought to a shambling halt. As clear as the reminder that the club is closing, the voice rang out:

“Who wants to shake for a drink?”