Las Vegas Press Club Circa 1963 Parties and Plays in Overton

This post may contain affiliate links or Google Ads and we may earn a small commission when you click on the links at no additional cost to you. As an Amazon Affiliate, we earn from qualifying purchases. This is at no additional cost to you and helps with our website expenses.

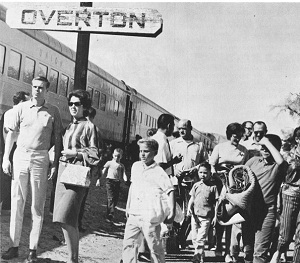

It looks like the Las Vegas Press Club sure knew how to have a good time back in 1963. In this episode of the Las Vegas Branding Iron Record 1963 report we are reprinting an article about a rollicking and fun trip that took press clubbers and guests to Overton, Nevada by way of the Union Pacific Railroad.

The Branding Iron had no qualms about pictures of big shots with a cigarette in one hand and a cocktail in the other. Staying sober didn’t appear to be an option for the adults on this invasion of Overton. This second annual excursion is chronicled below.

Into the Valley of Death

Like the Charge of the Light Brigade,

Into the Valley of Death,

Rode the Six hundred.

In this case, the Valley of Death was Overton, and environs.

The “six hundred” weren’t cavalrymen with drawn swords, but a trainload of press clubbers and guests waving their empty cocktail glasses at bartenders Jim Roberts, Clarence Harris, and Jimmy Williams, a ringer thrown in by the Shamrock Club.

Union Pacific Railroad had again surrendered to the pen and agreed to provide the coach cars for the frolicking 65-mile junket from Las Vegas to Overton, a tradition started last year which even the people who made the trip didn’t believe when they sobered up.

Two of Henderson’s plants, the American Potash and Chemical Co., and the Pacific Engineering Co. thought enough of the trip to chip in on the financing. Their apparent thinking was that it would have been worth any price to get that group out of town, even for a day.

By 9:30 a.m. the bleary-eyed railroad buffs and their house apes were swarming all over the UP depot at the foot of Fremont Street. Warren Neustrom, general agent for the UPRR, nervously bit his fingernails as the train began loading its human cargo. Then the human cargo started to get loaded.

Lofty Leon Potter, official Press Club photographer, took pictures of the celebrities (there weren’t any) as they arrived to watch in amazement at the proceedings. Potter was put on the train by a fork lift lest he topple the vista-dome lounge car onto the depot’s concrete apron.

The triple-header diesel revved up its engines and whined toward the city limits about 10:14 a.m. It clattered down the main line with a single purpose—to beat last years’ time to Overton. Nobody remembered what the time was.

At Moapa the block signals were red and yellow. The engineer slowed to a crawl and the train switched off to the Overton branch line, a section of UP trackage which has felt the crush of passenger cars only twice in the last 50 years.

Wheels screeched and whined around the curves, trestles creaked under the weight, and a half a dozen astounded deer hunters were backed up on a freeway detour trying to return to Las Vegas while the 13-car train crossed the highway.

By a sensitive radar warning system which would have made the Air Forces Early Warning system look like a child’s Christmas toy, the citizens of Overton were warned of the approach of the iron monster. George Sturtevant, American Potash field representative and railroad arranger, hurled a couple of empty Coors cans into the Muddy River. He thought they would float down through town ahead of the train’s arrival—giving further warning to the Overton citizens.

A few miles away, Norman Snoreen, chairman of the “go home press clubbers” committee of Overton, warned his reception horsemen to load their guns and mount their steeds. When the train rounded the last curve, the reception committee started shooting. The panic-stricken engineer tried to bypass the town, but some fool pulled the emergency cord, and the train screeched to a halt.

After two or three coronary cases were taken to the Overton Branch of the Southern Nevada Memorial Hospital, those who survived the reception headed for the recreational facilities of the community. Some even found their way to the B & J Club, where the Overton branch of the Harry James Orchestra was holding an off-hours jam session.

Jack Platt, the genial host at the Sportsman’ Bar, was recovering from surgery, so things weren’t so genial there. The deputy sheriff, who had been so cooperative the year before (he didn’t throw a soul in the Overton Branch of the Clark County jail) had fled town, at least for the duration of the invasion.

On the athletic field, George Foley, with his temperate disposition, was throwing baseballs at his wife, Irene. Dick Butcher, one of baseball’s all-time greats, ground out to Colin McKinlay, the PC’s honorary trainmaster who was reclining at the short-stop position with a water highball. Carl Apple, the Press Club’s accountant, lost track of the game score after the first inning—providing club members with a logical explanation for the monthly losses at the PC bar.

Madison Graves spent the four-hour stint in Overton exploring the train’s club car while his family visited Lake Mead. Harry Parker, the grand high potentate of the club, drank. Judge John Mowbray picnicked and cheered whenever anybody on either team struck out in the ball game.

Don Beale, a former newspaper reporter, made a significant showing as an umpire. His friends now know why he’s a former reporter. Hank Kovell, the Fremont Hotel’s media delegate, was frustrated. Nobody would tell him who “Sleep Out” Louis was.

Once relegated to their fate (anyone under 21 was confined to quarters) the residents of Overton responded with their hospitality. They provided rides to town from the railroad track, sold soda pop at a concession stand on the football field, let the “city kids” ride their horses and even danced with the tourists at the B & J Club.

As the warm October sun descended behind the ashen hills surrounding the not-so-quiet agricultural community, the engineer blasted his horn and it was “all ‘board.” The Press Club Special was returning home.

The finality provided one piece of amusement—although there was no Woody Cole and retinue along this year to flag down the train at Moapa.

A single pickup truck sped along a dirt road adjoining the UP right-of-way as the train pulled into the canyon leaving the valley. A lone man jumped from the truck, ran for the train and grabbed for the last car. He would have made it, except that some foolish railroad employee had closed all of the doors.

It must have been a long walk.